Minecraft Mob Identifier CS 175: Project in AI (in Minecraft)

Video

Main Project - Mob Identifier Iterative Image Dataset

Video Description

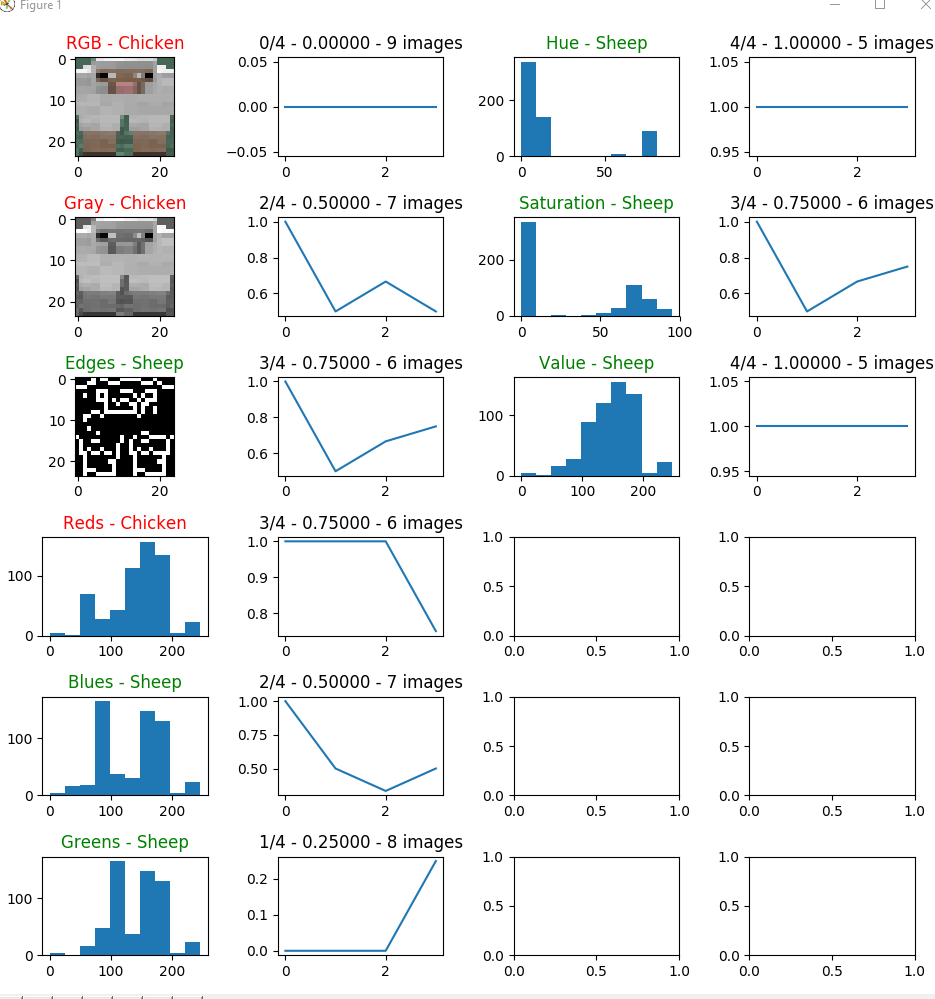

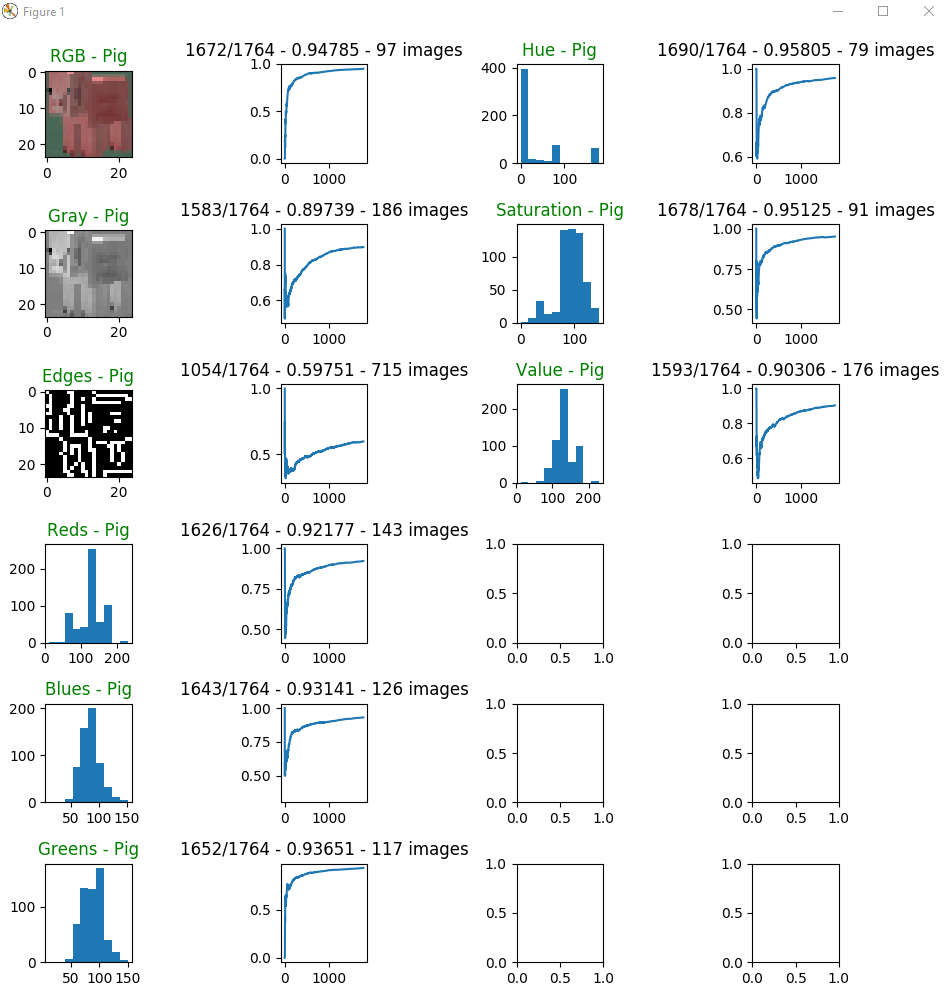

This video is showing the progress of our main project, being able to successfully identify mobs in an image based on pixel values alone (not using Malmo). We use Malmo to generate a static superflat world and use console commands to spawn mobs at varying distances around the user. We then take screenshots, crop the mob out, resize it to 24x24, and save it to our master dataset. We have several models that are testing at the same time, each instance using its own subset of the master image dataset. These subsets have their own model trained on varying image manipulations of the dataset (e.g. grayscale, edge detection). We show/graph these image manipulations along with the number of times the model classified correctly / the total number of times the model has made a prediction. Everytime the model incorrectly classifies a mob, it adds to the models training data. You can see in the video that at the start the graph the predictions are very sparatic but as the model build its dataset it starts learning and smooths out. The video is running a slowed version so we can view the graphs live. We can speed this process up by using a static dataset of images (no more waiting for mobs to be spawned) or by increasing the speed in game.

NOTE: There are 3 open subplots in the bottom right of the video because we were planning on adding more features to test.

Moonshot Project - Identifying Multiple Mobs

Video Description

We were experimenting with ways to find and identify multiple mobs in the same image. The video describes how we segmented the image into a 3x3. We also trained a model using segments of each mob (as opposed to the whole mob). We then took a cropping with multiple mobs in it, segmented it, then predicted the probabilities of each segment being each mob. Using these 9 different prediction probabilites, we tried to logically reason where the centroids of each mob were in the image. We then draw circles in the image where we thought these mobs were.

Project Summary

Goals

We wanted to be able to accurately identify mobs in the world using only images. Initially, we also wanted to be able to locate mobs in the Malmo world as well but as we came to understand the complexity of this problem we were forced to simplify it. The details of our attempts will be in the Approach section. Our simplified goal was to take an image of a single mob in a static superflat world and accurately classify what mob it was. This was very successful and easy to do. We wanted to make the project interesting so we asked ourselves “Just how many images does our classifier need to be accurate?” Our goal became how to run experiments in Malmo to test different datasets to see which one would be the smallest, most accurate, etc.

Dataset Creation

As we were figuring out how to approach the problem we tried MANY things. We first needed an image dataset. We ended up spawning an agent in a world with a single mob and taking thousands screenshots. We then applied different image manipulations to these images and trained different models to test which features/models to use. We decided to use sklearns Random Forest Classifier based on these results.

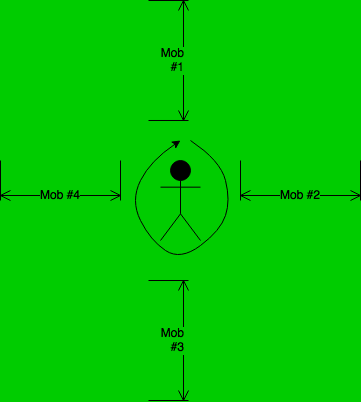

We then decided that we should automate an agent to build this dataset. We spawned an agent with 4 mobs surrounding the agent at fixed locations (random distance away from the agent) and continued to turn 90 degrees to look at the mob and take screenshots. When all 4 mobs were seen we sent a Minecraft console command to kill all mobs and repeated the process. Below is an image representation:

Iterative Model Training

As we create the above dataset we also run image manipulations on each mob we see (e.g. grayscale, edge detection). We use these image manipulations as the training features for different classifiers. These classifiers initially start with EMPTY subsets of the master dataset. When the model sees a label it has not seen before, it simply adds the label and its image manipulation to its feature data. If the model has seen the label before, it tries to classify that cropping. If it classifys WRONG, it adds the cropping to that models data. If it classifys RIGHT, it simply moves on. By doing this, we are performing hard negative mining. Meaning, we only add croppings to the models when we classify wrong. We only try not to add images of mobs that we know we can correctly classify.

Image Manipulations

Here is a list of image manipulations we currently use to train:

- Plain: no manipulation

- Grayscale: convert the image to grayscale

- Edges: Perform edge detection on the image

- Reds: Only use the red values of the image

- Greens: Only use the green values of the image

- Blues: Only use the blue values of the image

- Hue: Only use the hue values of the image

- Saturation: Only use the saturation values of the image

- Value: Only use the value features of the HSV image There were many more that we thought of but decided to show these in the video

Moonshot Attempt - Identifying Multiple Mobs

We attempted to find a solution for identifying multiple mobs and pin-pointing where the mob is in Minecraft so we could check our accuracy.

Identifying Multiple Mobs in a Cropping

As described in the second video above, we trained a model with segmented images and predicted their centroids.

Checking Accuracy

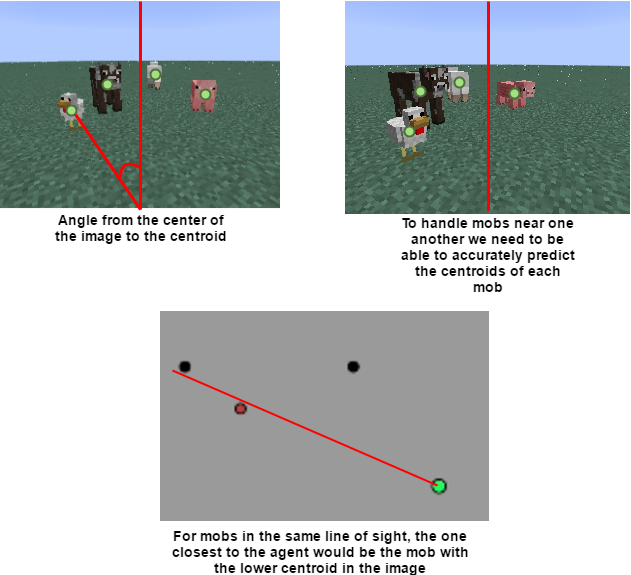

With the centroids from above, we would then query the Malmo grid and try to draw vectors from the image world to the grid world. We would use the knowledge from the center of the screen and the angle for which the centroid was predicted to draw a vector in the general direction of the mob in the image and map it to the grid world. We can use this information to face each mob we predict if we wanted to by using the angle as the yaw of which to turn. Below is an example of us drawing a vector from a centroid.

This became a large problem when we were trying to determine what our “cone of vision” was for our agent. This was critical it determined the accuracy of the centroids and their predictions. We first thought we could do this with Malmo by using the ObservationFromRay feature but this required that we actually look at the mob with our crosshairs in game. This feature gave us information like what the mob/block that we were looking at and its location in Minecraft. We could not use this reliably because during the time it would take to look at each centroid we predicted the mobs could have moved since then.

To show our progress on this, the video above shows how we went about segmenting the image and some actual centroids we were able to predict/draw. Due to time constraints we had to leave it at that. We did spend time researching how to get around this and experimented with different tools but we were not able to build a module that would solve this problem reliably.

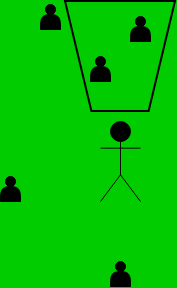

Malmo Integration

Our initial approach was to have the agent walk around and classify mobs but this proved quite the challenge because of the instance where multiple mobs are in the agents view. In addition, we included a minimap that showed the location of the mobs in relation to the agent and if they were classified or not. We had to change the agent to be stationary with only single mobs in its view so we could automate dataset creation and model testing. We also included graphs as visuals to show how the models were learning.

Approaches

Dataset Creation

At first we thought that we could scrape the images from the web (e.g. Google image search, Minecraft Wiki) but quickly found that there is too much noise in the datasets we created from that. At first they seemed okay but as you venture down the search results you can see the noise.

We then decided that we could get a lot more images from playing Minecraft and gathering screenshots for each frame. We decided to automate dataset creation by building an agent that would look at different mobs and crop them through a series of image manipulations.

Model Training

Here are the steps taken to process the frame given from Malmo to train each model:

frame = getFrame() # convert the frame from 1d array to image with channels

mob = cropMob(frame) # crop the mob

resized = resize(mob, (24,24)) # resize to 24x24 for consistency among crops

isNewLabel = checkLabelExists() # check if this label has been seen before

dataset.addImg(label, mob) # add mob cropping to master dataset

if isNewLabel:

# create new label with its image and retrain the model

for model in self.models:

manipulation = model.manipulate(mob) # apply manipulations to the mob

model.addImg(manipulation) # apply manipulations to the image and add to its training data

model.train()

return

# loop over different datasets, models, image manipulations

for model in models:

manipulation = model.manipulate(mob)

pred = model.predict(manipulation)

if pred == label:

# update statistics that it was correct

else:

# update statistics that it was wrong

model.addImg(manipulation)

model.train()

When we save the image to the dataset it is important to note that we do not save the whole image. We simply save the file path in a file that represents each model.

Finding Centroids

We reduced our problem of finding the centroids of each Minecraft MOB in an agents view to finding the centroids of each Minecraft MOB in the individual image croppings (of the agents view) generated using our cropper program. Our cropping program will generate two types of croppings: 1) A cropping containing one MOB (in which one centroid must be found), and 2) A cropping containing multiple MOBs (in which multiple centroids must be found). Below is a breakdown of the complications, methods and accuracies for both categories.

Single MOB croppings- Single MOB croppings were the easiest to find the centroid. There were next to no issues finding the correct location of the centroid, as essentially all of the cropping contained the MOB of interest and any parts of the cropping not belonging to MOB of interest, was deemed as background with near perfet accuracy. The only issue with finding a centroid for a single MOB cropping was a misclassification of the MOB. If the MOB belonged to the set {Cow, Mushroom cow, Pig}, then our random forest classifier predicted the MOB correctly close to 100% of the time. The only time that the random forest classifier had a harder time correctly classifying the MOB was when the MOB belonged to the set {Chicken, Sheep}, as both chickens and sheeps were of the color white, and were not always easily distinguishable.

Multiple MOB croppings- Multiple MOB croppings had essentially the same issues as single MOB croppings in terms of MOB classification. Hence, where our centroid program struggled the most, was not classifying the MOBs correctly, but in determing where and how many centroids to create. The way we determined the locations of our centroids is as follows: We split up the image cropping into 9 (3x3) equally sized image segments, and ran each segment through our random forest classifier to obtain the confidences that the classifier had, that each segment contained each particular MOB. We then created a centroid for every MOB and discarded the centroid if the total confidence of any particular MOB (Sum_over_all_segments(confidence_of_segment(MOB_type)) was below a particular threshold. After obtaining the believed to correct number of centroids, we proceeded to find the locations of each. This was done by placing the centroid in the center of the segment that had the highest confidence that the MOB was in that segment, and then adjusted the location based on the confidences of the segments around it. Since it was common that there were extra and/or misclassified centroids for MOBs in set {Chicken, Sheep}, we increased the threshold that the total confidences must exceed in order to keep the centroid for both chicken and sheeps. This led to better accuracy in MOB classifications and a reduction in amount of incorrect centroids being created, at the expense of not always finding a centroid of each MOB.

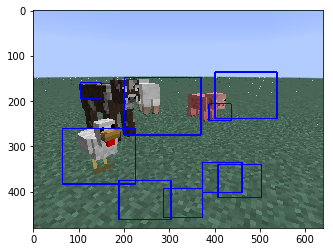

OpenCV Haar Cascades

Object Detection using Haar feature-based cascade classifiers is a machine learning based approach where a cascade function is trained from a lot of positive and negative images. It is then used to detect objects in other images. It will search the image for your trained object and draw a box around it if/when it thinks it seen it. Positive images are croppings of the image you want to detect. Negative images are of everything EXCEPT the object you want to detect. Both sets are grayscale.

We used our mob croppings as our positives and ~2000 images of an empty superflat world as our negatives. OpenCV then creates $x$ amount of image samples by superimposing the positive images onto the negative images with tunable variations (roations, pixel manipulations, etc).

We trained ~50 classifiers to try and detect single mobs (e.g. pigs) and mobs in general in the image. Each classifiers training time greatly depends on the parameters you set for the training. For us, it ranged from 5 minutes to 3+ days. The more samples you train with the longer it takes. We were expecting the high performance in the Minecraft world but each model we tried ended up with too many false positives. To combat this we did “hard negative mining” which was taking all the false positives the model predicted (images of the background) and using them as negative images when we retrained the model. For single mobs this produces about 70% accuracy of producing “good” bounding boxes. For multiple mobs the accuracy was very poor.

Types of training variations we employed

- positive image dimensions [24x24, 30x30, 40x40, 50x50]

- negative image dimensions [24x24, 40x30, 60x46, 80x60]

- number of positive images [50, 100, 200, 400, 800, 1000, 2000]

- number of negative images [50, 100, 200, 400, 800, 1000, 2000]

- number of hard negatives [50, 100, 200, 400]

- single mob positives

- all mob positives

- feature type [haar, lbp]

- positive images with background removed

- positive images with aspect ratio maintained

Sample command we used to train

opencv_traincascade -numStages 20 -minHitRate 0.999 -maxFalseAlarmRate 0.5 -w 40 -h 30 -data classifiers/40x30_30/all-mobs-10000 -vec all-mobs-10000.vec -bg all-negs.txt -numNeg 1800 -numPos 9000

Evaluation

Original Approach

We originally we had a static dataset containing ~5300 images and we were able to predict with surprising accuracy (~98%) for several different types of datasets (e.g. grayscale, edge detection). We wanted to see exactly how many of these images were required to achieve this level of accuracy.

Updated Approach

Every model that we have tested has its tradeoffs which can be seen in the statistics. For instance, using RGB values requires feature vectors of size 24x24x3 but has above average accuracy. We can make statements such as the following “The RGB model requires feature vectors of size 1728 while the Grayscale model only has feature vectors of size 576. Though, when using the RGB model it requires less than half of the number of images required by Grayscale and has greater accuracy.”. It was also surprising to find that only evaluating single color values had comparable performance to using all color values (e.g. RGB). In particular, using simple HSVs hue and saturation individually out performed using all RGB values.

Below are some screenshots of the model starting training and while it was in progress. We have some empty subplots because we were planning on adding more features to be tested (e.g. HSL, color histograms).

Start of the training

Training in-progress

We planned on running each model until the number of correct predictions / total number of predictions was around 99%. Once this happened we would compare its accuracy and number of images needed for training the original static dataset. Unfortunately we ran out of time!

References

Here are a list of references we frequently used: